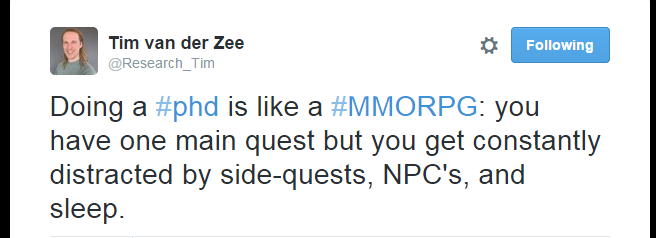

A while ago, my co-worker and fellow blogger Tim posted a tweed likening getting you PhD to a MMORPG. I thought this was a funny and also pretty accurate description and today I want to write about one of my favourite PhD side-quests: Teaching.

For context, I write this as a full time PhD student who is not expected to teach that much. About 10% of your appointment is a normal amount of teaching for PhD students in the Netherlands. This may be very different from the situation of some of you. Some of you may be teachers/PhD candidates whose main quest is actually teaching. If it is, my post may not be that useful for you, but hopefully you have some nice tips to add for those of us who are inexperienced teachers.

Before I started my PhD I worked as a Teaching Assistant in various courses for two and a half years and I’ve been involved in the teaching of two different courses since I started my PhD. I love teaching and think it is very rewarding, but it is also very tiring and time-consuming. Today I share some tips to make your teaching experience as good as possible:

Educate yourself

If you’re a new PhD student teaching a course or tutorial may seem intimidating. Especially if you have never taught before! There are several ways to educate yourself.

You can try and see if your university offers workshops or courses for teachers to improve their general teaching methods. You can also talk to more experienced co-workers and see how they approach their teaching. This can be in general, or related to the specific course you’re expected to teach. Experienced teachers hopefully will have hands on information that you can use while preparing for teaching.

Be well prepared

A thorough preparation is vital, especially if you expect that you will be teaching a course several times. Of course preparation is time consuming, but it is a timesaver if you are able to take your slides from previous semester. A thorough preparation can also help with nerves on your side. If you are really well versed in the subject you will be teaching, you will feel more secure standing in front of the students.

Plan!

Teaching can be a serious time consumer. Especially if you have to grade student work and provide individualised feedback. One tip that a co-worker gave me is to set aside a specific moment during the week for these type of activities. That way you know how much work you actually have to do and you have some control over the amount of time you spend. Try to be realistic in your planning. I for one know that I cannot go straight from teaching to being focused on my research, so I’ll plan for some transition time as well.

What’s in it for you(r research)?

When your teaching duties consist of thesis supervision it may be possible for you to combine teaching and your own research. Often, the students will get involved in your project and (hopefully) collect some of your data. But even when your teaching is not that directly linked to your research there may still be links. Maybe the content of the course you’re teaching is closely related and you can use your theoretical insights during instruction. But even if there is no way to connect your teaching to your research, teaching a course is relevant to your personal and professional development.

Enjoy it

Whatever you do, enjoy your teaching experience!

Happy questing and hopefully this side-quest will help you level up!

Have you been teaching and what are your tips for PhD students who are starting to teach?

Recent Comments