Many first-year higher education students experience the transition from secondary to higher education as challenging. To facilitate this transition, universities offer mentoring programs. How can such a mentoring program be designed in an effective way? This literature overview outlines effective ingredients of mentoring programs.

How does mentoring help to foster student success?

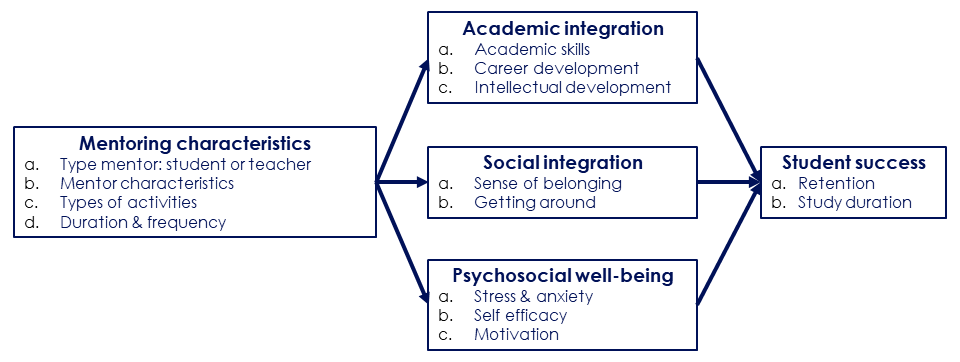

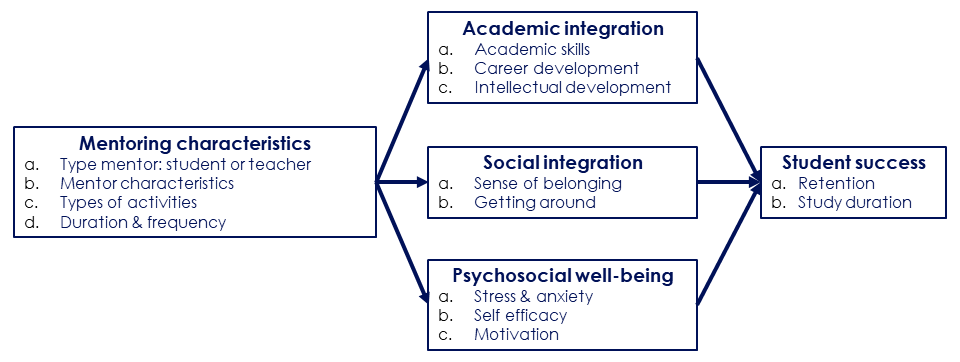

Mentoring can be defined as “a formalized process based on a developmental relationship between two persons in which one person is more experienced (mentor) than the other (mentee).” (Nuis et al., 2023, p. 7). Based on a synthesis of the literature, I have developed the following conceptual model that relates mentoring to student success.

The relationship between mentoring and academic success can be explained through three mediating factors: academic integration, social integration, and psychosocial well-being (Lane, 2020). Academic integration involves academic knowledge and skills (Crisp & Cruz, 2009), career path development (Crisp & Cruz, 2009), and student identification with the norms of the university and their field of study (Tinto, 1975). Academic integration ensures that the student is committed to the goal of successfully completing their studies, thereby lowering attrition (Tinto, 1975). Social integration involves sense of belonging, with peers and within the wider university community, and the ability to find one’s way within the university (Lunsford et al., 2017; Tinto, 1975). This type of integration is also hypothesized to reduce attrition (Tinto, 1975). Psychosocial well-being involves issues such as stress, resilience, self-efficacy, and motivation (Law et al., 2020).

Does mentoring work?

Many studies show that mentoring is effective in increasing student success (Andrews & Clark, 2011; Campbell & Campbell, 1997; Crisp & Cruz, 2009; Eby et al., 2008; Gershenfeld, 2014; Jacobi, 1991; Lane, 2020), and studies confirm that the mechanism through which mentoring is effective operates through the mediating factors (Lane, 2020; Lunsford et al., 2017; Webb et al., 2016). However, effects seem to be generally small (average effect size .08; Eby et al., 2008).

What are characteristics of effective mentoring?

Below, I discuss characteristics of effective mentoring programs for which evidence is available. It is important to keep in mind that it is the combination academic, social, and psychosocial support that makes a mentoring program effective (Lane, 2020). Among the characteristics of effective mentoring, the role and person of the mentor stands out: This appears the most important ingredient of any mentoring program.

Type of mentor: peer or teacher

The two main types of mentors are senior peers and faculty members. Peer mentors may be more suitable for providing social and psychosocial support (Leidenfrost et al., 2017), may be more available and approachable, and therefore easier to confide in (Lunsford et al., 2017). However, for academic integration and academic success peer and teacher mentoring appear equally effective (Lunsford et al., 2017).

Mentor characteristics

What are attributes of effective mentors? I discuss a number of them:

Helpfulness: The mentor’s helpful and empowering attitude makes a significant contribution to the psychosocial well-being of a mentee (Lane, 2020). Mentees even prefer a mentor who considers their needs and helps them make choices above an empathetic mentor (Terrion & Leonard, 2007).

Role model and openness: Mentors must be able to act as role models and reflect on their own experiences and challenges (Holt & Fifer, 2018). Furthermore, if a mentor can open up to the mentee in a healthy way, and sees the relationship as a joint learning process, this can lead to a relationship in which there is room for growth (Terrion & Leonard, 2007).

Self-efficacy: Mentor’s self-efficacy seems to be an important predictor of perceived support. Careful selection, training and guidance of mentors helps to ensure appropriate self-efficacy of mentors (Holt & Fifer, 2018).

Availability and approachability: Sufficient availability and good approachability of mentors leads to higher satisfaction, both for mentors and mentees (Ehrich et al., 2004; Terrion & Leonard, 2007).

Experience with mentoring: It seems that mentors do not need to have previous experience as mentors (Terrion & Leonard, 2007).

Type of activities

There is some evidence about which activities have proven effective. Social integration is promoted by facilitating contact between fellow students and with the mentor, by encouraging conversation and discussion, by exchanging ideas and experiences, and by supporting mentors and fellow students in problem-solving (Ehrich et al., 2004). Providing constructive feedback, and avoiding judgmental feedback, fosters academic integration and psychosocial well-being (Ehrich et al., 2004; Leidenfrost et al., 2011). Academic integration can be promoted by helping students to interpret and respond to feedback (Law et al., 2020), in self-regulated learning in general, in writing, and in exam preparation (Andrews & Clark, 2011; Holt & Fifer, 2018). This latter type of support requires tacit knowledge, which peer mentors can share from first-hand.

Duration & frequency

There is no consistent evidence about the duration and frequency of meetings (Lane, 2020). On the one hand, more contact between mentor and mentee leads to more perceived support (Holt & Fifer, 2018; Andrews & Clark, 2011) and higher student success (Campbell & Campbell, 1997). On the other hand, if the mentee is satisfied with the mentor’s support, the time the mentor spends with the mentee does not lead to more mentee satisfaction (Terrion and Leonard; 2007). So while the quantity of contact is important, the quality of contact appears equally significant.

Conclusion

Based on the literature, the conclusion seems justified that the person of the mentor and how the mentor fills the support are the most important ingredient of any mentoring program: A helpful and open mentor who is approachable and able to empower the mentee can be a powerful source for effective mentoring.

References

Andrews, J., & Clark, R. (2011). Peer mentoring works! Aston University.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Campbell, T. A., & Campbell, D. E. (1997). Faculty/student mentor program: Effects on academic performance and retention. Research in Higher Education, 38(6), 727-742. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024911904627

Crisp, G., & Cruz, I. (2009). Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50(6), 525-545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2

Eby, L. T., Allen, T. D., Evans, S. C., Ng, T., & DuBois, D. L. (2008). Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(2), 254-267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.005

Ehrich, L. C., Hansford, B., & Tennent, L. (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 518-540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161×04267118

Gershenfeld, S. (2014). A review of undergraduate mentoring programs. Review of Educational Research, 84(3), 365-391. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313520512

Holt, L. J., & Fifer, J. E. (2018). Peer mentor characteristics that predict supportive relationships with first-year students: Implications for peer mentor programming and first-year student retention. Journal of college student retention : Research, theory & practice, 20(1), 67-91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025116650685

Jacobi, M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 61(4), 505-532. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543061004505

Lane, S. R. (2020). Addressing the stressful first year in college: Could peer mentoring be a critical strategy? Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 22(3), 481-496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025118773319

Law, D. D., Hales, K., & Busenbark, D. (2020). Student success: A literature review of faculty to student mentoring. Journal on Empowering Teaching Excellence, 4(1), 22-39.

Leidenfrost, B., Strassnig, B., Schabmann, A., Spiel, C., & Carbon, C.-C. (2011). Peer mentoring styles and their contribution to academic success among mentees: A person-oriented study in higher education. Mentoring & tutoring, 19(3), 347-364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2011.597122

Lunsford, L. G., Crisp, G., Dolan, E. L., & Wuetherick, B. (2017). Mentoring in higher education. The SAGE handbook of mentoring, 20, 316-334.

Nuis, W., Segers, M., & Beausaert, S. (2023). Conceptualizing mentoring in higher education: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 41, 100565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100565

Terrion, J. L., & Leonard, D. (2007). A taxonomy of the characteristics of student peer mentors in higher education: findings from a literature review. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 15(2), 149-164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260601086311

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89-125. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543045001089

Webb, N., Cox, D., & Carthy, A. (2016). You’ve got a friend in me: The effects of peer mentoring on the first year experience for undergraduate students Paper presented at the Higher Education in Transformation Symposium, Oshawa, Ontario, Canada

Recent Comments