As I have written here before, I am a great fan of the possibilities offered by Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). Having taught multiple languages in various contexts in my time, there is something very appealing about what Kees de Bot once referred to as “The Sneaky Way” (2007: 276) of helping learners acquire a language while using it to focus on curriculum content. To those with a background in second language acquisition, it just makes so much sense!

If it makes so much sense, why is it so hard for CLIL teachers to live up to the expectations outlined in the theoretical and practical literature on CLIL? In the Dutch context, several studies have drawn attention to the apparent shortcomings of CLIL classroom practice (e.g. de Graaff et al. 2007, Koopman et al. 2014, van Kampen et al. 2017, Oattes et al. 2018) when held up against models based on theories of language pedagogy and second language acquisition. Clearly, for the teachers involved in those studies, CLIL as we understand it does not make as much sense as it does to me.

Every teacher a language teacher?

As a teacher educator in the World Teachers Programme, I have the privilege of working with enthusiastic and talented new teachers from a range of disciplines. While collaborating on a forthcoming publication recently, Liz Dale and I noted that the student teachers we each work with are most receptive to the idea of CLIL when we approach it in a way that leaves space for their disciplinary identity (Dale et al., 2018). Rather than preaching the adage “every teacher is a language teacher” and asking students of biology, history or computer science to conform to the ideals that title implies, I find it more helpful to ask students to consider the roles of language and communication as integral aspects of their existing expertise in their subject. “Every discipline has its own ways of thinking, behaving and communicating” seems a more constructive approach that does justice to teachers’ real areas of expertise. As a teacher educator, it is not my job to turn all teachers into language teachers, but to help them recognise and make salient to learners (Ball et al., 2015) the language and culture of their subject in ways appropriate to their age and level of readiness (see Coyle & Meyer’s (2021) Lego model for an illustration).

A new perspective on perspectives

This idea that each subject has its own “culture” (Coyle, 2015) is a crucial aspect of disciplinary literacies. This is a similar view to that taken in Fred Janssen’s perspective-oriented education, which takes as its basis the idea that different disciplines view phenomena through different lenses. What disciplinary literacies adds to the discussion, however, is the idea that different perspectives are communicated in different ways and through different means (or ‘text types’). A social scientist is likely to use different sources and produce different types of output than a mathematician or an art historian, and will therefore need support from a teacher who is an expert in the genres of their subject. This applies in foreign-language CLIL settings, but also in mainstream settings: after all, who speaks ‘Geography’ or ‘Physics’ as their home language?

So what about the language teacher?

Does this mean that language teachers have to relinquish their dream of teaching language “The Sneaky Way”? I think not. In fact, I would argue that a disciplinary literacies approach finally offers language teachers the opportunity to realise that dream within their own subject. Language teachers are experts in content areas such as literature, linguistics, culture and intercultural communication (Meesterschapsteam mvt, 2022). Rethinking language curricula around content such as these would reposition language subjects as disciplines in their own right, with their own perspectives and disciplinary literacies (see also an earlier post on this).

Having established that teachers are well-equipped to support development of disciplinary literacies from their own subject perspectives without compromising their disciplinary identity, the question remains as to how best to support them in finding the best ways to do so. Do you have ideas for how to approach this or are you interested in carrying out research? Get in touch with your ideas via t.l.mearns@iclon.leidenuniv.nl.

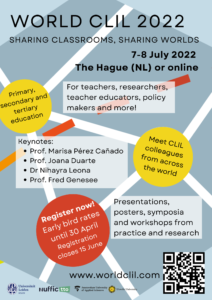

And… Join us at World CLIL 2022!

Want to connect with colleagues in the international CLIL community? On 7-8 July this year, ICLON will team up with Nuffic to host the World CLIL conference in the Hague. We promise a packed programme with a wide range of workshops on location and over a hundred presentations and symposia available to both on-location and online participants. Registration is open until the 15th of June, but why wait? See www.worldclil.com for more information.

References

Ball, P., Kelly, K., & Clegg, J. (2015). Putting CLIL into Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Bot, K., 2007. Language Teaching in a Changing World. The Modern Language Journal, 91(2), pp. 274-276.

Coyle, D. (2015). Strengthening integrated learning: Towards a new era for pluriliteracies and intercultural learning. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 8(2), 84-103, doi:10.5294/laclil.2015.8.2.2

Coyle, D., & Meyer, O. (2021). Beyond CLIL: Pluriliteracies Teaching for Deeper Learning. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dale, L., Oostdam, R., & Verspoor, M. (2018). Searching for identity and focus: towards an analytical framework for language teachers in bilingual education. Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 21(3), 366-383 DOI: 10.1080/13670050.2017.1383351

de Graaff, R., Koopman, G. J., Anikina, Y., & Westhoff, G. (2007). An Observation Tool for Effective L2 Pedagogy in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 603-624. doi:10.2167/beb462.0

van Kampen, E., Meirink, J., Admiraal, W., & Berry, A. (2017). Do we all share the same goals for content and language integrated learning (CLIL)? Specialist and practitioner perceptions of ‘ideal’ CLIL pedagogies in the Netherlands. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, Online first. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1411332

Koopman, G. J., Skeet, J., & de Graaff, R. (2014). Exploring content teachers’ knowledge of language pedagogy: a report on a small-scale research project in a Dutch CLIL context. The Language Learning Journal, 42(2), 123-136. doi:10.1080/09571736.2014.889974

Meesterschapsteam mvt (2022). Visie op de toekomst van het curriculum Moderne Vreemde Talen. Accessible via https://modernevreemdetalen.vakdidactiekgw.nl/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2022/04/Basistekst-visie-4.4.pdf

Oattes, H., Oostdam, R., De Graaff, R., Fukkink, R., & Wilschut, A. (2018). Content and Language Integrated Learning in Dutch bilingual education. How Dutch history teachers focus on second language teaching. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 156-176. doi:10.1075/dujal.18003.oat