“In classrooms on all populated continents of the world, learners are engaged in learning content in a language that they do not speak at home. Depending on where you are, you may know this as Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) or under another name.

“In classrooms on all populated continents of the world, learners are engaged in learning content in a language that they do not speak at home. Depending on where you are, you may know this as Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) or under another name.

Through such approaches, learners develop as language users but also have the opportunity to broaden their horizons and to grow as global citizens. In these uncertain and even tumultuous times, having the knowledge, skills and attitudes to communicate across and within cultures and communities has never been more important.”

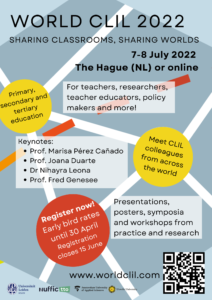

So read the text on the homepage of World CLIL 2022: a two-day conference that took place this month, dedicated to bringing together members of the extensive community of researchers, teachers and teacher educators who are engaged in CLIL and other multilingual approaches to teaching and learning throughout the world. The goal: Learning from and with each other in all our diversity, and in celebration of the diversity of our learners.

Based on the overwhelmingly positive response from participants and speakers, this goal seems to have been achieved.

Celebrating diversity

The conference theme referred to diversity among colleagues and also among learners. This was the common thread running through the four keynote addresses. Prof. Marisa Pérez-Cañado kicked off with an energising and engaging exploration of questions of “diversity, inclusion, and elitism” in CLIL settings, and of the extent to which old stereotypes still ring true. Prof. Joana Duarte followed this later with a reflection on how an asset-based approach to diversity, coupled with attention for global citizenship and intercultural communication, can help us to truly integrate the content, communication, cognition and cultures present in our classrooms.

On Day 2, Nihayra Leona focused on linguistic diversity, and how much there is to learn from the expertise and experiences of CLIL colleagues working in linguistically rich settings such as the Caribbean. Heading into the final afternoon, Prof. Fred Genesee rounded things off by exploring and dispelling the myth of the incompatibility between bilingualism and special educational needs.

Between these talks, we also saw a diversity of content, be explored in over 100 presentations, symposia, posters and workshops focusing on research, practice and combinations of both.

Together at last

In spite of apprehension earlier this year, when we feared Omicron might put an untimely end to years of planning and preparation, the hybrid conference ultimately boasted nearly 400 attendees, stemming from 44 different countries and six continents. Nearly two-thirds of the delegates attended the event in person, at Leiden University in the Hague. Among the onsite participants, there was a clear sense of excitement and readiness to once again engage in networking and professional learning by coming together in person.

That said, World CLIL would have fallen short of its goals if not for the 144 delegates who attended from afar. Online presenters and audience members attended sessions together with colleagues on location: a challenge to facilitate but well worth the investment. In addition, online delegates were offered the opportunity to meet informally in a ‘Meet&Greet’ networking activity. In the breaks, interviews conducted by ‘roving reporters’ in The Hague offered online participants a flavour of the onsite experience.

A further enrichment were the nineteen colleagues who had received a scholarship due to challenging local or personal circumstances, and were offered free online access. Due to the conference’s limited budget, this would not have been possible had the programme been fully offline.

And next… World CLIL 2024?

Now that we have got the ball rolling, it is time to hand over the baton. Our colleagues in Sheffield, UK, are already working hard on the preparations for their own CLIL 2023 event. After that, perhaps there is room for World CLIL 2024 in Edinburgh, Hong Kong, Willemstad or elsewhere…?

Through regular meetings in diverse locations, I for one hope that the international CLIL community will continue to grow in both its diversity and its unity, as we continue to learn by sharing our classrooms and sharing our worlds.

World CLIL was hosted by Leiden University, in collaboration with Nuffic, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Utrecht University and the Dutch Network of Bilingual Schools.

Special thanks to the rest of the organising committee, to the PhD researchers from ICLON and students from the World Teachers Programme and the HvA who helped with the organisation and moderation, and to all who shared their work at this event. Interested in seeing what was on the programme? It is still available via www.worldclil.com.

Photographs by Peter Sansom.

Recent Comments