Authors: Nivja de Jong and Tessa Mearns (members of Meesterschapsteam MVT)

One time is not enough, two times is a trend, and three times is a tradition

In June 2017, the LLRC (Language Learning Resource Centre) was ‘launched’ with a full-day programme by and for language teachers, language teacher educators, and language learning researchers. Most of those present were from Leiden University, unsurprising as the LLRC has as its central aim to bring together language teachers and researchers from the different Leiden University institutes involved in teaching languages: LUCL, LIAS, ATC, ICLON and LUCAS. On June 7th, 2019, the third full-day conference was hosted by the LLRC, this time on the topic of intercultural communicative competence with a focus on higher education. Professor Michael Byram (emeritus professor, Durham University) was the invited speaker of the day. Anyone who has ever heard of the term “intercultural communicative competence” knows the stature of Prof. Byram. Although again, most people came from Leiden University, both presenters and attendants were now more diverse.

“Why should the biologists get all the fun?”

This was a question posed by Prof. Byram during his keynote. He referred to the fact that in CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning), as the acronym already clarifies, it is usual to teach content whilst teaching language. So if biologists teach about biology whilst teaching language, what (fun) topics can and should language teachers use?

When teaching language, students and teacher(s) use language, and this language that is used is always about something. Teachers can to some extent choose the content for which the language will be used. If we agree that being a communicative competent user of a language, also means to understand (something about) the (sub-)culture of the language, it becomes apparent that a form of content in the language classroom can and should be “culture”. So biology teachers do NOT get all the fun. Language teachers can claim an enormous amount of interesting topics to teach, and this in turn will lead to learners that are more interculturally competent and language-aware.

A shared vision

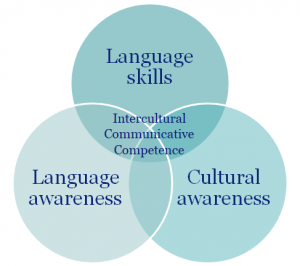

The same note was struck in the last lecture of the day, by the Meesterschapsteam MVT, who showed their model on language teaching for the Dutch curriculum: intercultural communicative competence is the core competence, and this core evolves from three overlapping learning outcomes: cultural awareness, language awareness, and language skills, as depicted in the figure below.

Figure: Learning outcomes for a content-rich Modern Languages curriculum (adapted from Meesterschapsteam MVT’s vision on the future of Modern Languages education)

A question of ‘perspective’

Apt content to foster these competences can be specified by approaching ‘language’ from different academic perspectives: language as a structural phenomenon, language as a cognitive phenomenon, and language as a cultural phenomenon. Insights from such theoretical models have direct and fun implications for language teachers in their everyday practice. Instead of borrowing topics from other subjects (reading and talking about “panda’s eating bamboo”, “(made-up?) hobbies”, “the environment”), teachers can choose topics that are relevant for language: therefore choosing topics that are about structures of languages (from phonetics to discourse), about cognitive phenomena (from top-down processing while listening to Zipf-distributions or child language learning), about social phenomena (such as status of dialects, the effect of language and its power), and about cultural phenomena (ranging from stereotypes about cultures to literature and other forms of art). Biologist teachers get all the fun? No way! Language teachers get all the fun!

Support for a content-rich vision

The rest of the day’s presentations illustrated through practical examples how language teaching can include teaching about culture and developing intercultural competence (ICC). From the multilingual school to partnerships across international borders, language-and-culture-integrated literature teaching, assessment of ICC, to ICC training for university staff and students, the day presented us inspiration from a whole host of research findings and good practices.

Reform can only succeed if there is support at grassroots level. If the attendance and enthusiasm with which this conference was received are anything to go by then perhaps the vision of content-rich language education is not so far off the mark.

Next year’s LLRC Day will be held in June 2020 and centre around the theme ‘The interplay between practice, research, and theories in L2 learning’. Keep an eye on the LLRC website for more information.

Recent Comments